By JK Clarke. . .

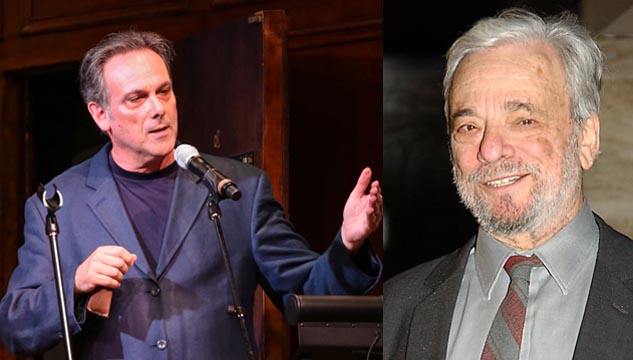

AJ Holmes had a more successful and eventful career in his 20s than most writers/performers could hope for in a lifetime. In the past decade, he played Elder Cunningham in The Book of Mormon on the US and International tours and eventually on Broadway; played in the US tour of Young Frankenstein and composed music for such productions as A Very Potter Musical, Me and My Dick and Twisted. A full slate, to be sure, and undoubtedly a remarkable and sometimes anguishing way to grow into full adulthood. In his new one-man musical, Yeah, But Not Right Now— playing through October 17 at the SoHo Playhouse—he lets us in on some of his angst and travails in something of a too-revealing musical confessional.

Holmes was kind enough to point out the predominant shortcoming of both his life and the show somewhere at the midway point: “this is the part of the show where I’d like you to feel bad for me for having the greatest career opportunity . . . Everybody say, ‘aw, he got rich really fast’.” By highlighting the obvious, he’s attempting to engender sympathy for the things in his life that went south. But it’s hard. He really was privileged, he really did get up the hill faster than most people. But that’s not the main problem. What’s hard to sympathize with are his wrong turns. They’re no different than the wrong turns any of us make (he cheated on a girlfriend; he frequented massage parlors that provided “happy endings” . . . okay, so what?). The problem is that he thinks that these things are unique and that they deserve our “Aww.” They aren’t and they don’t. Just about every uncomfortable circumstance he brings up would be better dealt with in therapy, or just accepted as a part of growing up. They certainly aren’t situations riveting enough to put on stage.

None of this would be a problem if the musical numbers were good enough to distract us. But they generally feel either banal or incomplete. Self-interrupted numbers that feel uninspired and haphazardly written, as if random thoughts tossed-off in a sparsely filled night club at closing time. One song, “Fuck Boi,” is a perfect example. (“I gotta sing with honesty/So, if you know the symptoms/And you don’t want a fuckboi/You probably shouldn’t fuck . . . with me.”) Punctuated with lighting effects and sounding like he’s muttering mostly to himself rather than singing, the song provides no expansion on the thought that he might be someone whose primary interest is sex (again: so what?). What’s more, he probably should be aware that most audience members over 50, which may turn out to be a large percentage, probably have no idea what that Millennial slang even means.

Someone should advise Holmes that with his toothy good looks and Broadway bona fides, he needn’t spend money on sex workers for something he should be able to obtain quite easily for free. And if not, he shouldn’t try to assuage his guilt in front of a paying audience that tunes out in the first fifteen minutes (or spends the rest of the show heckling, as was the case when I attended), but should spend the money he saves on a therapist who will listen attentively for the full hour and help him gain a few points of emotional IQ.

It’s unfortunate that director Caitlin Cook didn’t encourage Holmes to re-work his script, taking out flat jokes and directionless turns. He really does exude charm and has a wonderful voice. An entertaining program would have been most welcome. As it is he risks being upstaged by one of the many guests who open the show with a fifteen to twenty minutes set. And it almost seems as if he’s aware of the show’s shortcomings. Toward the end he tells the audience: “So, you can like me, you can hate me. I can’t manipulate you anymore. If I ever even could.” The self-awareness is valuable, but he failed to consider one other option: What if we just don’t care?

Thru October 17 at SoHoPlayhouse, 15 Vandam Street, NYC