JOHN LEE BEATTY, PORTRAIT OF THE DESIGNER AS A YOUNG MAN: A LOST INTERVIEW

Part 1

As Told to Samuel L. Leiter

In 1980, I interviewed John Lee Beatty in his apartment on West 86th Street. At the time, he was just emerging as one of the most brilliant young set designers in the American theatre. Subsequently, of course, he became perhaps the most successful and well-known designer of his generation.

Using the method employed by famed New Yorker writer Lillian Ross in her exceptional book (with Helen Ross), The Player: A Profile of an Art, I converted the interview into a first-person narrative as told by John himself.

This was an ad hoc interview, not one I’d been assigned by any publication. I was planning a book of such theatrical interviews and this was to be the first. Ultimately, I did only one other, of the actor-director-writer, Simon Callow, 13 years later. I was so busy with other projects in those days that these fell into the abyss, where they remained until I came across them during our Covid-19 quarantine, while organizing all my papers.

This being as good a time as any to make them public, I’m providing the Beatty one here, just as it was written 40 years ago. I haven’t updated the prefatory bio information, which you can check on here or at any number of online sites. Hopefully, the Callow interview will follow when time permits.

This is going to be a 15 part series. Hope you enjoy reading it

***

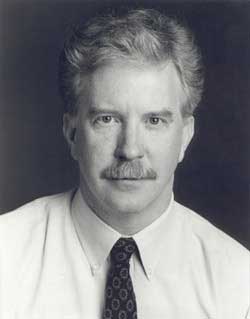

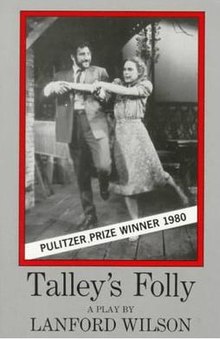

Stage designer John Lee Beatty began his professional career in New York in 1973. His first designs were for the Manhattan Theatre Club, where he has since designed many shows. His closest affiliation has been with the Circle Repertory Company, where he has collaborated with director Marshall Mason on close to 20 productions, including the premieres of several Lanford Wilson plays. Among his Broadway credits are Knock, Knock, The Innocents, Ain’t Misbehavin’, The Faith Healer, The Water Engine, Whoopee!, and Talley’s Folly, for which he won the 1979-80 Tony Award. His other awards include the Obie, for distinguished Off-Broadway work. Beatty also has designed for America’s leading regional theatres.

Over six feet tall, with thick red hair and a mustache to match, Beatty speaks in a soft, drawling manner and is an extremely gentle and shy person. Handsome, sincere, and completely dedicated to his craft, he nevertheless projects an image of complete ingenuousness, as if he himself cannot believe the good fortune that has come his way. This interview was conducted several months before he won his first Tony.

***

I was born in April 1948 in Palo Alto, California. My father was Dean of men at Stanford at the time. We lived there a year, I think. Then we moved to Southern California, to Claremont, which at the time was a town of maybe five or six thousand, a very small town, an orange-growing town with five colleges. That’s where I grew up.

My father was a professor of English lit and my mother had been a government professor and then a housemother. So the housemother married the Dean of men and romance was born. My mother, a real dynamic lady, did a lot of work in civic leadership positions, league of women voters, city council-type of stuff, girl scout leader; a very goody-two-shoes lady. My father was writing his thesis and my mother was typing it, and that was the days before Xerox.

Even today, when I hear a typewriter late at night, it’s a security sound to me because it’s like my mother typing as we went to sleep. Every night when I was a child. Even sometimes on vacation they’d take the typewriter.

So, I grew up in an academic environment, surrounded by a lot of books and very intelligent people. I have a sister and she’s very bright, too. I’m not stupid at all, and I’m the dumbest one.

Ours was the perfect postwar family. You know, they had the two kids, one boy and one girl, one in 1946 and one in 1948, and they bought the little redwood house with the garden. I think there was a style in the fifties, an American dream thing, right after the war, when people wanted picket fences. You can see it in the clothing styles, in the domestic architecture. It’s almost clichéd male-female.

We went to Sunday school, in little ties and jackets. Everything was very—I don’t know if you have it here [in New York]—“Barbara Ann Bread Company”; smiling girls and boys with freckles. I, of course, was particularly appropriate. I had all those attributes.

I know it’s disappointing to find out, but there really was no great exposure to the world of art, to painting, in my childhood. I drew a lot as a child and my parents were very “raised consciousness” for that time. We were never allowed coloring books. I had to make my own drawings. My mother wouldn’t allow me to do anything else. We weren’t allowed comic books. We were always encouraged in art, but the main thing that happened was when I was eight or nine. My father took a sabbatical and we spent a year traveling around Europe. That was the real starting point, I think, of my sort of visual awareness of the world and styles.

I’m constantly grateful to my parents for that kind of exposure. Before we went, all I knew of Europe was that it rhymed with syrup and was across the ocean. When we returned I could tell you the three styles of English country churches and the difference between the styles of Paris Opera and Covent Garden. It was the kind of crazy change that can only happen to a child.

I was always a special child, a little dreamy, a little off on my own. Also, I started being interested in theatre when I was seven, before we went to Europe. My parents took me to see (this is such a cliché) Mary Martin on stage in Los Angeles. It was the tryout of Peter Pan and we had seats in the balcony. I still remember the exact position. And I loved it, absolutely adored it, and I came home wanting to be a set designer at age seven. I didn’t know what a set designer was but I knew exactly what I wanted to be involved with.

My imagination took hold—I wanted to fly just like any child would want to fly after that—but I also wanted to fly on the wire. I thought the wire was the greatest thing. All the stage mechanics and the sort of fantasy, the reality of the fantasy on stage, was wonderful to me.

I designed Peter Pan a lot as a child, with construction paper, cardboard, and blocks. Then later, I did bigger versions of Peter Pan with appliance cartons and created lovely effects. I can only imagine what they looked like. I refuse, for obvious sentimental reasons, to see the present production. [Ed. This was the revival starring Sandy Duncan that ran at the Lunt Fontanne Theatre from September 1979 to January 1981.]

I would love to design Peter Pan but I can wait. I designed it for years before I knew there were other shows you could design. I knew there were other plays. I’d seen Macbeth and I’d seen a lot of other Shakespeare things, but my design consciousness did not allow me to design other shows until much later.

(To be continued.)