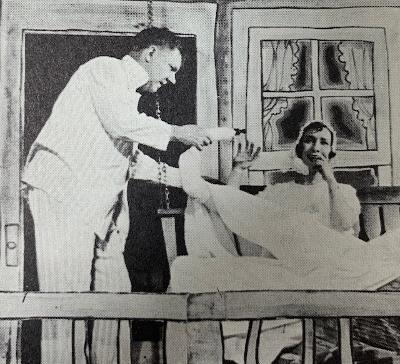

Helen Hayes, Otto Kruger in To The Ladies

By Samuel L. Leiter

When this series began, my intention was to offer installments in which I described, for each season from 1920-1921 on, a small selection (five, when possible) of plays, musicals, revues, and revivals. The biggest problem I’ve run into has been deciding what to select. Today, for example, I cover five new plays of 1921-1922, a season in which, depending on the source, new plays totaled 142 (Variety), 130 (Best Plays), or 135 (my Encyclopedia of the New York Stage, 1920-1930).

To simplify the job, I’ve ignored many of the best-known ones, such as all of Burns Mantle’s Ten Best Plays (Anna Christie, A Bill of Divorcement, Dulcy, He Who Gets Slapped, Six-Cylinder Love, The Hero, The Dover Road, Ambush, The Circle, and The Nest). Some of these, of course, may barely be known, even to buffs.

Instead, with so many other worthwhile plays available, I’ll look at less familiar examples, omitting such titles as Abie’s Irish Rose, Getting Gertie’s Garter, Back to Methuselah, Bulldog Drummond, The Hairy Ape, and The Verge. I apologize to those who would like to be reminded of them and their local reception. If you’ve never heard of Thank You, The Demi-Virgin, The Intimate Strangers, Kiki, and To the Ladies, allow me to introduce you to them.

Edith King & Frank Moore in Thank You

Thank You (Longacre Theatre, 10/3/21, 257) was a successful comedy, by Winchell Smith and Tom Cushing, satirizing church practices and limning some charming rural types. The action occurs in small-town Connecticut, where David Lee (Harry Davenport) ekes out a meager living as pastor of St. Mark’s Parish. Much of his income derives from being a “thank you” man to those who hand him small sums at funerals and weddings.

An orphan niece (Edith King) arrives to spur him on to demand better treatment, but her smart Continental ways incite the vestrymen to start a scandal and rid the town of her uncle. A young millionaire (Donald Foster) sides with Rev. Lee; a year later he’s a well-paid religious leader who is quoted nationally. As you’ve already guessed, the millionaire and the niece wind up in each other’s arms.

Robert Allerton Parker observed that the play was cleverly contrived with all the stock conventions. Still, he couldn’t hide the fact that the authors “succeed in arousing and holding our interest, and . . . in the end, if you are honest, you must express your gratitude . . . for an evening of real amusement.”

To the Ladies (Liberty Theatre, 2/20/22, 128), by the formidable George S. Kaufman and Marc Connelly, was a delightful follow-up to the authors’ recent Lynn Fontanne starrer, Dulcy, with the scatterbrained wife of that piece replaced here by a helpmate worth her weight in gold. Helen Hayes was marvelous as Elsie Beebe, the Southern-belle wife of Leonard (Otto Kruger), a piano salesman. She works for his advancement without telling him about it, arranging for him to give an after-dinner speech at a company banquet directly after a talk by a rival salesman aiming for the same promotion. This scene becomes a delicious parody of all such affairs.

Leonard falls apart when he hears his rival give the same cribbed speech he himself had prepared from a manual. Elsie comes to the rescue, apologizes for his “laryngitis,” and gives a brilliant impromptu chat of her own that makes her spouse look great, confirming Kaufman and Connelly’s patronizing theme that behind every successful man there is invariably a clever woman.

This “uncommonly sound and amusing little play,” as Ludwig Lewisohn called it, being truthful, funny, ironic, and satiric, was viewed as an improvement over Dulcy and provided “an occasion of genuine and quite uproarious jollification” for Alexander Woollcott. Helen Hayes’s performance was “admirable in its sincerity and resource, and her pathetic moments have the true moving note,” announced Arthur Hornblow. Hayes was so anxious to do well that she told the writers she could sing and play the piano to perform a spiritual as part of the role. Since she didn’t actually have those skills, she quickly hired a teacher to take lessons.

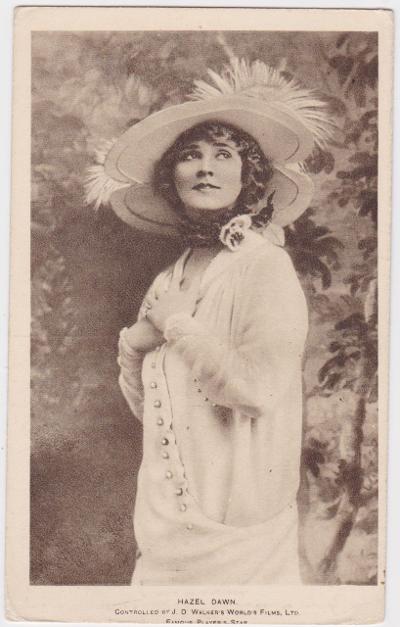

Glenn Anders & Hazel Dawn in The Demi-Virgin

The ever-popular sex farce was alive and well in the 1920s, as in Avery Hopwood’s The Demi-Virgin (Times Square Theatre, 10/18/21, 268), a popular example based on an uncredited French original. It came to New York with a scandalous reputation attendant upon its having been closed by the Pittsburgh police. Despite its attempted naughtiness, however, the worst the critics could say, as per Louis V. De Foe, was that “Its name is the most provocative detail.” Percy Hammond thought it was “as roguish as a nude cadaver.”

Glenn Anders

Produced by A.H. Woods, whose career was built on similar bedroom romps, The Demi-Virgin was a flimsy attempt to expose the immorality of the Hollywood film colony, with its reputed absorption in fleshly concerns. Its plot revolves around the interrupted marriage of film stars Gloria Graham (Hazel Dawn)—a name that one day would belong to an actual movie star—and Wally Dean (Glenn Anders), a relationship that crumbles when an old flame of his calls him in the wee hours of his wedding night. Gloria, obviously, turns green with jealous ire. Thereafter, Hollywood knows her as “the demi-virgin.” Wally’s efforts to win back his estranged bride succeed when the studio forces them to finish the film they were making before they broke up.

The most risqué scene involved a game of strip-poker, whose presence led the Times to refuse to advertise the show by its title. Woods then advertised with an ad mentioning how many people had attended the show at the Eltinge Theatre (to which it had moved). The result was a surprisingly robust run.

Elizabeth Patterson, Glenn Hunter, Clare Weldon, Billie Burke, Frances Howard, Alfred Lunt in The Intimate Strangers

Booth Tarkington’s The Intimate Strangers (Henry Miller’s Theatre, 11/7/21, 91), produced by Florenz Ziegfeld, Abe Erlanger, and Charles Dillingham, among the leading producers of the day. It was a lighthearted romantic comedy that couldn’t sustain the charm and originality of its opening act but nevertheless pleased by its superb acting and disingenuousness. Constructed on a fragile plot, it revealed its author “never in a hurry, never in the least self-conscious, and never dull,” according to Kenneth Andrews. Alexander Woollcott said it ranged “from utterly charming to rather stupid,” but was ultimately disappointing. It had been written specifically for Alfred Lunt, to capitalize on his success in Clarence, to whose title role his present one bore a strong resemblance.

Two strangers, Ames (Lunt) and Isabel (Billie Burke, Ziegfeld’s wife, who was Glinda, the Good Witch, in The Wizard of Oz movie), meet at a country railroad station when stranded there for the night They fall in love, although Ames is momentarily bedazzled by Isabel’s flapper niece (Frances Howard), who arrives in the morning. Isabel, a sure-footed matron, manages to recapture Ames’s interest, and marriage is definitely in the offing.

Lunt (who got engaged to Lynn Fontanne during the run) and Burke made a delightful romantic duo and were responsible for a large share of the play’s appeal. After Fontanne viewed a performance, Lunt asked for her opinion of his work and she responded honestly: “You work too hard. Act being relaxed,” to which she later said, “He didn’t like that at all.” Still, one reason for their eventual success as acting partners would be their ability to criticize one another frankly.

Lenore Ulric in Kiki

Finally, there was Kiki (Belasco Theatre, 11/29/21, 580), David Belasco’s adaptation of French playwright Andre Picard’s boulevard comedy, put through an “American deodorizing process,” as Arthur Hornblow described it. This process removed all taint of the off-color from what was originally a more realistic view of its milieu’s morality.

Belasco also produced what Woollcott called an “abominable” translation in which the language of the Parisian working class became a strange collaboration between French argot and Broadway showgirls. “T’en fais pas, I’ll give him a dirty wallop,” went one line. The play itself was second-rate but its title character allowed Lenore Ulric to inspire critical joy.

Kiki is a gamine, a chorus girl with a crush on her theatre’s manager (Sam B. Hardy), who is married to but estranged from the star performer (Arline Fredericks), who wants to get him back. In the best-liked scene, Kiki, faced with a choice between becoming the mistress of Baron Rapp (Max Figman) or returning to the streets, pretends to be the victim of a cataleptic trance. The play ends with Kiki and the manager happily in love.

Writing of the star’s acting, Ludwig Lewisohn declared, “Miss Ulric’s playing is perfect. She has made over her body. Every gesture, every step, her very nerves and sinews are drenched with Kiki.” Before it closed, Kiki had become the longest running Broadway play based on a French original.

Next: what to choose for our look back at the musicals of 1921-1922.