Sally, Irene and Mary. Song sheet for “Time Will Tell.”

By Samuel L. Leiter

If prizes were ever handed out for the best musical theatre seasons of the 1920s, 1922-1923 wouldn’t come close. Not only wouldn’t it be considered in the running, it would be mired in the decade’s lower half with little to redeem it, at least from a long-term view. The five musicals I’ve chosen to represent the season from the thirty that were produced are likely to ring few bells except among a small coterie of the cognoscenti, but it’s always interesting to see what they were and how they were received.

Their titles? I suggested six last week: Sally, Irene and Mary; Orange Blossoms; Up She Goes; Little Nelly Kelly; Liza; and Wildflower, chosen mainly for their popularity in that otherwise bleary season (for musicals, not plays, as the last installment revealed). One will not make the cut but, unless you cheat, you’ll have to wait to find out which.

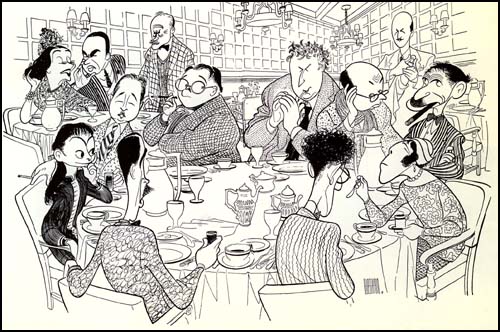

So, following the bouncing ball of chronology, we begin with Sally, Irene and Mary (Casino Theatre, 9/24/22, 318), a title based on previous hits that would be like someone decades later calling their show Dolly, Mame and Gypsy. Sally had starred Marilyn Miller, Irene had starred Edith Day, and Mary had starred Janet Velie, each being a hit built on a Cinderella theme, their success inspiring the Shuberts to produce this egregiously commercial spinoff, with music by J. Fred Coots, lyrics by Raymond Klages, and Jean Brown, Kitty Flynn, and Edna Morn playing roles loosely based on the originals.

Eddie Dowling

This was enough to create a smash hit and make a star of vaudeville player Eddie Dowling, who collaborated on the book with Cyrus Wood. The inspiration was a sketch Dowling had done at the Winter Garden. Two decades later he would direct the premiere of The Glass Menagerie and play Tom Wingfield opposite Laurette Taylor.

A three-and-a-half-hour Irish stew of songs, dances, and Lower East Side sentimental comedy, Sally, Irene and Mary followed the fortunes of three tenement girls who are discovered while performing on their neighborhood streets and become Broadway stars, with stage door Johnnies clamoring for their favors. Mary is courted by Rodman Jones (Hal Van Rensselaer), son of her rich landlady (Winifred Harris), but her affections are really for Jimmie Dugan (Dowling), a political aspirant who has found her out in her new milieu, one that makes him ill at ease. Mary overcomes his hesitation, and romance flares on the fire escape, to which she comes in search of him. A tenement wedding scene, with nuptials celebrated by all three titular heroines, provides a grand finale.

“It is a plummy show,” bubbled Alan Dale, “full of material. It is a glossy, shiny . . . show [with] plenty of music and considerable pep.” There was a return engagement that ran sixteen performances at the Forty-fourth Street Theatre from 3/23/25. In 1925, a silent movie version starring Constance Bennett, Joan Crawford, and Sally O’Neill hit the screens, with a talkie (singie?) coming in 1938, starring Alice Faye, Joan Davis, and Marjorie Weaver.

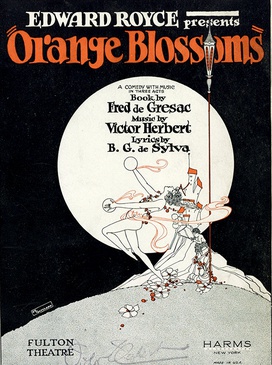

Orange Blossoms poster

Orange Blossoms (Fulton Theatre, 9/19/22, 95), the entertaining Victor Herbert operetta that introduced “A Kiss in the Dark,” one of the composer’s great waltzes, was based on The Marriage of Kitty, a 1903 adaptation of a 1902 French hit called La Passerelle. Its star, who sang “A Kiss in the Dark,” was soprano Edith Day, who, after her 1919 success in Irene, was becoming one of Broadway’s most popular musical stars. It also featured singer-dancers Queenie Smith and Hal Skelly. Orange Blossoms was the final Victor Herbert show produced before he died.

The ultra-familiar plot—Fred de Gresac (Mrs. Victor Maurel), co-author of La Passerelle, wrote the book—focuses on Kitty’s (Day) agreement to marry, then divorce, a nobleman named Baron Roger Belmont (Robert Michaels). The baron wants to circumvent a will and marry a Brazilian dancer, Helene de Vasquez (Phyllis LeGrand), prohibited by the will from becoming his first wife. The expected resolution finds the baron falling in love and remaining with his “temporary” wife.

This inane plot was thought the cat’s pajamas for a musical. With Herbert’s music to sustain it, Orange Blossoms became a “Rolls-Royce of musical comedies,” according to the Herald. Played against the “beautiful backgrounds of gray and moon color” as the Times described the set, designed by the estimable Norman Bel Geddes, Orange Blossoms was a lovely show both visually and audibly. Director-choreographer Edward Royce, said Kenneth Macgowan, “has never created dances with such ingenuity and effectiveness or woven them into the action of a show so cleverly.” The musical also marked the producing debut for this experienced director of Florenz Ziegfeld revues

If the title Little Nellie Kelly (Liberty Theatre, 11/13/22, 276) strikes a chord, it may be because it was turned into a colorful 1940 Hollywood movie, starring Judy Garland. Still, the original, with book, lyrics, music, and co-direction by George M. Cohan, was the longest running in his glittering career, and proved he still had the moxie that made him the Mr. Broadway of his time.

This amusing musical parody of mystery plays inspired the Tribune’s reviewer to claim: “The charm of Mr. Cohan’s play is that he never takes the book seriously. He lets no opportunity slip by without spoofing his own efforts and taking the playgoers into his confidence.”

Little Nellie Kelly.

Song sheet for “Nellie Kelly, I Love You”

Dedicated to Cohan’s parents, Jerry and Nellie—the names shared by the romantic leads—this musical firecracker was in the beloved Cohan tradition of dynamite dancing, supercharged sentimentality, and explosive humor. The author borrowed “all the standard props of the successful musical comedies of the last two or three years,” claimed the Tribune, to tell the story of Irish-American police Captain Kelly’s (Arthur Deagan) daughter, Nellie (Elizabeth Hines), clever department store salesgirl. Nellie is loved by the wealthy Jack Lloyd (Barrett Greenwood) as well as her jealous childhood sweetheart Jerry Conroy (Charles King). Jerry’s suspicions of Jack are tied into a plot about a string of pearls, stolen at a party, with Jerry, until near the end, suspected of the theft. Nellie, attracted at first to Jack’s material abundance, nevertheless chooses the earthier appeal of Jerry.

The show’s popularity was attested to by its being done the following year in London, as well as on tour, and as far away as Australia. Jerry’s song, “Nellie Kelly, I Love You,” later heard in the George M. Cohan bio-musical, George M., was the biggest hit, although his “You Remind Me of My Mother,” sung here in early 1920s style by Henry Burr, also had success. As so often, the show’s movie version—although retaining several of the original songs—radically changed the storyline.

In 1921, Shuffle Along’s success had made the viability of Black-created, Black-performed, Black-produced Broadway musicals readily apparent. One of the decade’s several attempts to replicate its popularity was Liza (Daly’s Theatre, 11/27/22, 172), book by Irvin C. Miller, music and lyrics by Maceo Pinkard (a first-class songwriter who co-wrote “Sweet Georgia Brown”), with additional songs by Nat Vincent.

Liza didn’t run as long as its famous predecessor but it met with nearly as favorable a critical reception. There was scant attention paid to its “rather weak” book, as the World called it, and the comedy pickings, with Black actors in blackface, were spare, and the show’s format and look were uninspired and more vaudeville-like than straight musical comedy. But Liza—originally titled Bon Bon Buddy, Jr.—had drive and pace and rhythm and spirit enough to power the Great White for several profitable months.

What plot there was dealt with the collection of money for a monument to the late mayor of Jimtown (a standard location for such shows), giving the local dandies and other smooth denizens a chance to line their pockets with the donations. When the populace notices that Dandy (Thaddeus Drayton), schoolteacher beau of Squire Norris’s daughter, Liza (Margaret Simms), seems to be prospering, suspicions of graft begin to emerge (the Squire is behind the monument plan). These suspicions, however, are allayed and the lovers announce their nuptials. One funny scene took place in a cemetery where a couple of grave robbers were scared silly by a ghost.

The show’s outstanding feature was its dynamic chorus routines, including the “Charleston Dancy,” leading the World to call it “the fastest dancing show ever seen on Broadway.” He went on: “These agile colored youngsters dance with their hands, legs and bodies and no steps seem too difficult for them to do it in unison.” Walter Brooks directed and probably did the uncredited choreography.

Edith Day, Guy Robertson in Wildflower.

Once again, Edith Day beamed sunlight on a hit Broadway show when she appeared in Wildflower (Casino Theatre, 2/7/23, 477), an operetta with book and lyrics by mainstays Otto Harbach and Oscar Hammerstein II and music by Herbert Stothart and Vincent Youmans (despite it being mistakenly credited by the shamefaced Times to Rudolf Friml).

Day, in another outrageously banal plot, played Nina Bandetto, an attractive, hot-blooded peasant girl of Lombardy, heiress to a fortune she can’t collect until she proves herself a polite, mild-tempered young lady—with no outbursts—for six months. The machinations to get her to blow a gasket is presented in several scenes by persons wishing to inherit the money in her stead, most notably her cousin Bianca (Evelyn Cavanaugh). Still, the “wildflower” manages to hold on and win her inheritance and nab her lover Guido (Guy Robertson) into the bargain.

Arthur Hornblow delighted in the “intelligible book, music that is more than ordinarily fresh and original, and . . . cast of capable performers.” The Times, while regretting the flimsy comedy ingredients, deemed this “an adroit and workmanlike example of . . . musical comedy.” After the show closed, the sun went down on Edith Day’s Broadway career when she moved to London, where she quickly rose again to brighten the West End.

As you can see, Up She Goes didn’t go up on this shortlist of 1922-1923 musicals. Not that including it would have made much of a difference. Next time out, “Leiter Looks Back” will look back at the season’s top musical revues, an assortment of possibilities ranging from Black shows like Strut Miss Lizzie and Plantation Revue to conventional ones like Spice of 1922 to big name ones like George White’s Scandals and the Ziegfeld Follies to mammoth spectacles like Better Times. Decisions, decisions.