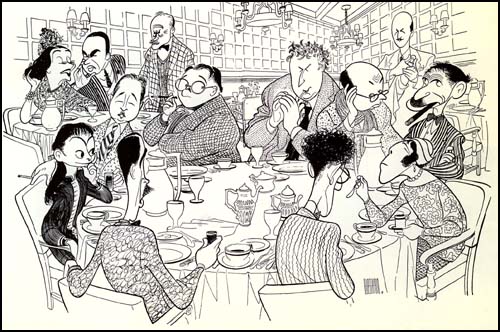

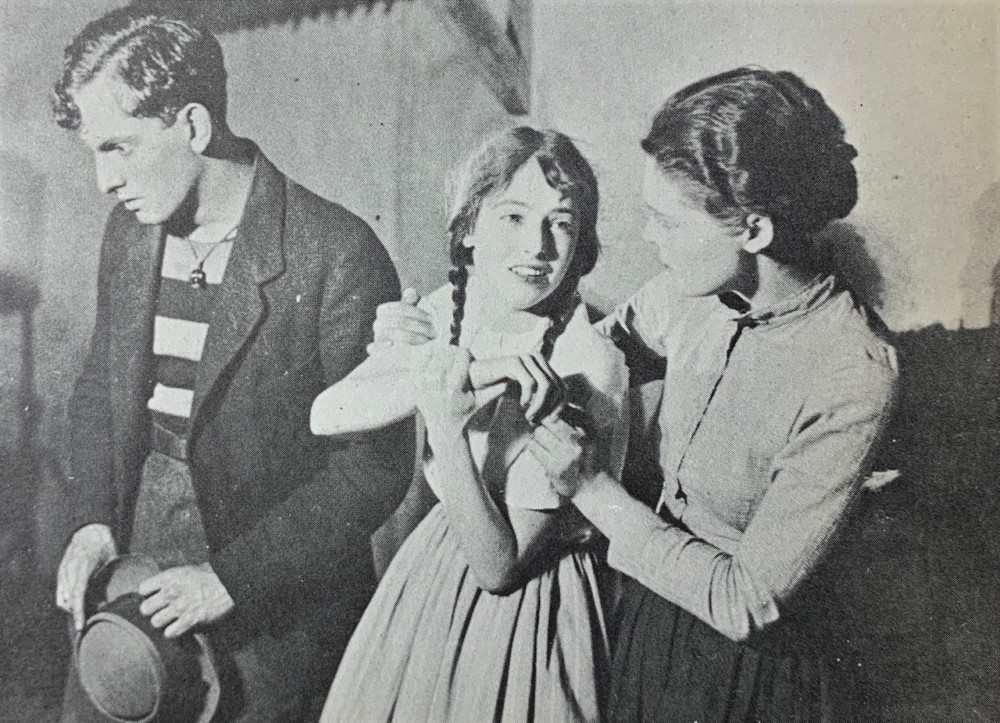

Louise Closser Hale -Jack Bohn – Catherine Calhoun Doucet -William E. Holden – Beth Varden – Carroll McComas in Miss Lulu Bett

By Samuel L. Leiter

Leiter Looks Back looks back again to the 1920-1921 New York theater season, for which we’ve already commented on two commercially successful shows. Following our plan, I’m offering three more straight plays, one predominantly commercial, the others more artistically ambitious.

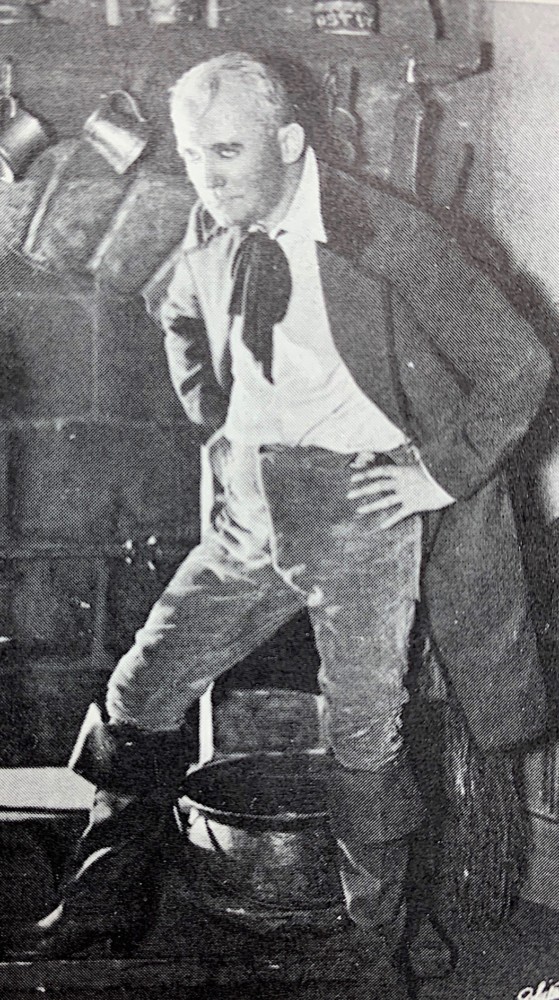

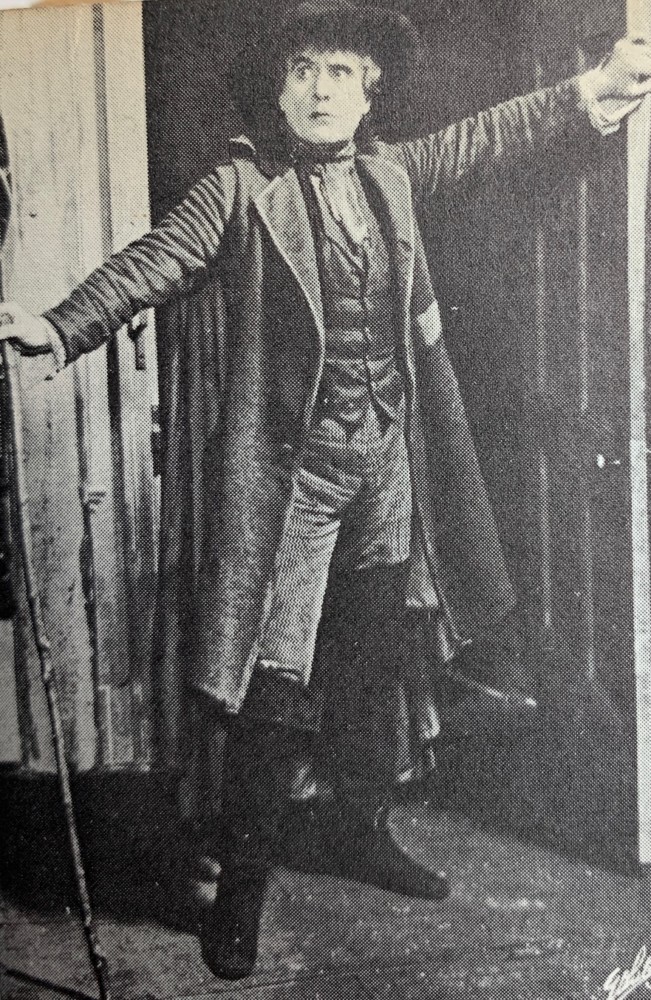

George M. Cohan – The Tavern

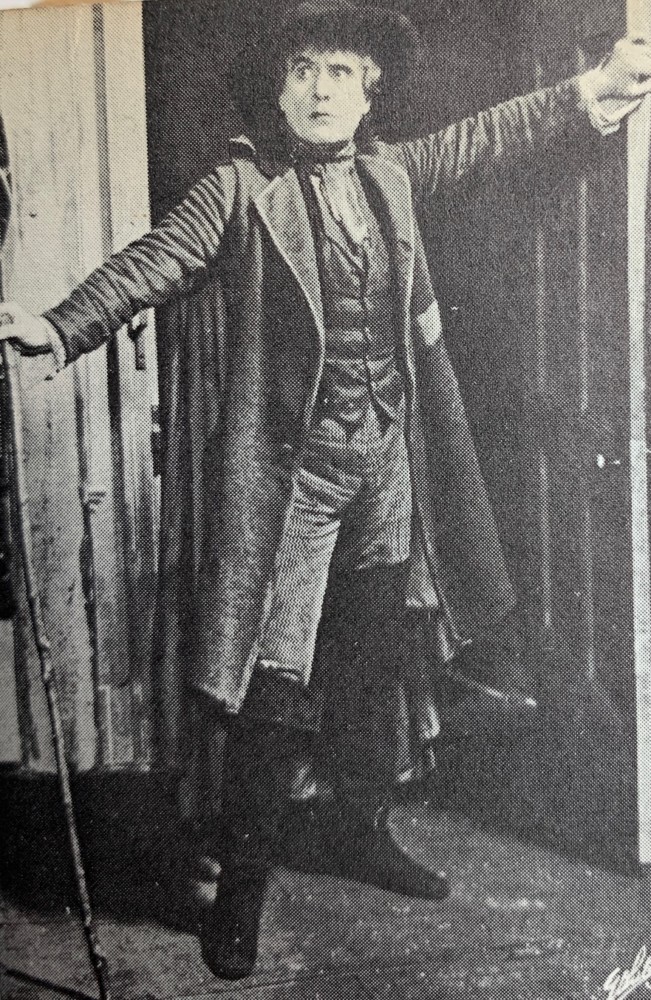

Arnold Daly – The Tavern

The Tavern, never made into a movie, was credited to a Cora Dick Gannt, but its real author was the beloved playwright, songwriter, and song and dance man George M. Cohan, who also directed. It opened at the George M. Cohan Theatre on September 27, 1920, ran 252 performances, and became a favorite of amateur and professional companies for years to come.

Gannt had written a seriously intended work called The Choice of a Super-Man. This first version had been a romantic whimsy with a fascinating role, the Vagabond, a mysterious figure, played by Arnold Daly. However, when Cohan grew dissatisfied with the work during the tryouts, he rewrote the piece from scratch as a ne plus ultra melodramatic spoof.

Audiences ate it up but the critics found it a bit chewy. Every shopworn spring in the old-fashioned mellers was sprung in the plot about a motley assortment of characters who turn up one terribly stormy night at an early nineteenth-century tavern. They include the Vagabond, a governor (Morgan Wallace), his wife (Lucia Moore), his daughter (Alberta Burton), her fiancé (William Jeffrey), and a wronged woman (Elsie Rizer). A caretaker (Joseph Allen) gets to speak words that became a catchphrase: “What’s all the shootin’ for?” At length, everyone falls under suspicion of foul play, the Vagabond observes all with wry humor, and boundless complications ensue until the melee of events is explained as the doing of the Vagabond, an escapee from the local booby hatch.

Daly seemed too old and fat for the romantic role he was portraying. It was only when Cohan himself took over on May 23, 1921, for 27 performances at the Hudson Theatre that the true amusement in the piece became clear. Avoiding Daly’s straight interpretation, he guyed it up, offering “a typical Cohanesque performance—a swinging, broadly etched interpretation that grew in subtlety as the play progressed,” wrote the Times.

Cohan had begun rehearsals with an unfinished script. As new material was completed it was handed to the cast. Thus, Daly didn’t learn until just before the opening that the character he was playing was intended to be an escaped lunatic. Cohan triumphed when he revived the play for 32 performances at the Fulton Theatre in 1930.

William E. Holden – Catherine Calhoun Douce – BrighamRoyce -Carroll McComas – LoisShore – Louise Closser Hale – BethVarden in Miss Lulu Bett

More artistically respectable was Miss Lulu Bett, a comedy by Zona Gale, which won the 1921 Pulitzer for drama. Gale based it on her own novel, completing the script in eight days. It opened under Brock Pemberton’s direction at the Belmont Theatre on December 27, 1920, garnering 201 performances. Despite its Pulitzer, however, Burns Mantle ignored it as a Ten Best candidate.

Gale’s Cinderella story concerns the 34-year-old Lulu (Carroll McComas), a spinster who works as a drudge in the home of her self-satisfied sister, Ina (Catherine Calhoun Doucet) and brother-in-law, Dwight (William E. Holden). Her payment is her room and board. Dwight’s friendly brother, Ninian (Brigham Royce), shows up and a mock marriage ceremony between him and Lulu is arranged by Dwight, who announces that the nuptials are binding. But soon afterward, Dwight informs Lulu that he’s already married but believes his wife to be dead. Lulu leaves him and returns home, where her relatives now fear for their reputations.

As originally produced, the ending had the first wife turn out to be alive, leading Lulu to turn her attention to another admirer. As revised after the opening, the play concluded happily by offering proof Ninian was indeed a widower.

Unusually, Miss Lulu Bett actually premiered at Sing Sing in a performance for inmates just one night before it came to Broadway. It appealed for the veracity and humor of its small-town, somewhat Dickensian characters, but had a fair number of detractors, some claiming it was inferior to the novel. Gale defended her revision on the basis of popular opinion, which rejected seeing Lulu facing an uncertain future. But a few defended the original, Ludwig Lewisohn, for example, complaining that the revision betrayed the plot’s inevitability.

The silent film version, produced not long afterward, can be seen here.

Joseph Schildkraut, Eveline Chard, and Eva Le Gallienne in Liliom

Miss Lulu Bett soon faded, unlike Liliom, which remained a staple and still sometimes is revived, even after its fame became bound to the classic Rodgers and Hammerstein musical it inspired, Carousel. A Hungarian work by Ferenc Molnar, it premiered in Budapest in 1909, but found success there only after World War I ended. Its English version had a hit run of 300 performance after opening at the Garrick Theatre in a Theatre Guild production, directed by Frank Reicher, on April 20, 1921. During the run, it transferred to the Fulton Theatre.

Selected by Mantle as a Ten Best, it employs poignancy and satire to tell its tale of the crude carnival barker, Liliom (“roughneck”; Joseph Schildkraut), a flirt who wins the love of the housemaid Julie (Eva Le Gallienne), whom he beats, despite his affection for her. She gives up her job to be his bride. Her pregnancy inspires Liliom, needing cash, to commit robbery with his pal, Sparrow (Dudley Digges). When the attempt fails, Liliom kills himself rather than go to prison.

The play shifts to a fantasy set in heaven, where Liliom appears before a police court judge (Albert Perry), who says he can return to earth in fifteen years for one day to redeem his soul. On that day, the unregenerate thief returns, having stolen a star for his daughter (Evelyn Chard). She doesn’t recognize him and he even slaps her. After he’s gone, Julie learns of the incident and realizes who her daughter’s visitor was.

Eva Le Gallienne, Joseph Schildkraut, and Helen Westley in Liliom

Liliom’s experimental blend of fantasy and reality was a harbinger of new directions in modern drama. Its writing, translation, direction, décor (by Lee Simonson), and acting gained widespread admiration. Edmund Wilson’s wrote: “Liliom . . . is such a very good play that one hardly knows what to say about it. The theme is slight and rather sentimental, but it handled so deftly and lightly and redeemed with such sharpness and wit that the result is a drama of dignity.” Nowadays, of course, Liliom’s sympathetic treatment of a brutish hero who strikes his own wife and daughter but is nonetheless excused because his violence springs from love has made the play (and even Carousel) a subject of feminist debate.

Interestingly, an earlier mounting starring John Barrymore had been abandoned when director-producer Arthur Hopkins decided it would flop. Schildkraut persuaded the Guild to stage it on the basis of a German version he had read. He also convinced the company to cast Le Gallienne. She recalled in At 33 how brilliantly Schildkraut acted on opening night. Of herself, she said she “was playing badly.” “I was so nervous that my mouth was parched and dry. I was tied up in a thousand knots. . . . It was a nightmare,” which led to her surprise when the critics lauded her success.

Only several months later, on September 9, 1921, Off Broadway’s Irving Place Theatre offered a Yiddish version that ran simultaneously with the Guild’s. The Times noted a rude and unruly audience but praised the Hungarian actor, Martin Ratkay, for his portrayal of Liliom.

Two old films of Liliom are on YouTube: Frank Borzage’s weak Hollywood version of 1930 is here, and Fritz Lang’s artier French version of 1934 is here, although the copy is poor.